for an overview of Buddhism

In the sixth century before the Christian era, religion was forgotten in India. The lofty teachings of the Vedas were thrown into the background. There was much priestcraft everywhere. The insincere priests traded on religion. They duped the people in a variety of ways and amassed wealth for themselves. They were quite irreligious. In the name of religion, people followed in the footsteps of the cruel priests and performed meaningless rituals. They killed innocent dumb animals and did various sacrifices. The country was in dire need of a reformer of Buddha's type. At such a critical period, when there were cruelty, degeneration and unrighteousness everywhere, reformer Buddha was born to put down priestcraft and animal sacrifices, to save the people and disseminate the message of equality, unity and cosmic love everywhere.

Buddha's father was Suddhodana, king of the Sakhyas. Buddha's mother was named Maya. Buddha was born in B.C. 560 and died at the age of eighty in B.C. 480. The place of his birth was a grove known as Lumbini, near the city of Kapilavastu, at the foot of Mount Palpa in the Himalayan ranges within Nepal. This small city Kapilavastu stood on the bank of the little river Rohini, some hundred miles north-east of the city of Varnasi. As the time drew nigh for Buddha to enter the world, the gods themselves prepared the way before him with celestial portents and signs. Flowers bloomed and gentle rains fell, although out of season; heavenly music was heard, delicious scents filled the air. The body of the child bore at birth the thirty-two auspicious marks (Mahavyanjana) which indicated his future greatness, besides secondary marks (Anuvyanjana) in large numbers. Maya died seven days after her son's birth. The child was brought up by Maya's sister Mahaprajapati, who became its foster-mother.

On the birth of the child, Siddhartha, the astrologers predicted to its father Suddhodana: "The child, on attaining manhood, would become either a universal monarch (Chakravarti), or abandoning house and home, would assume the robe of a monk and become a Buddha, a perfectly enlightened soul, for the salvation of mankind". Then the king said: "What shall my son see to make him retire from the world ?". The astrologer replied: "Four signs". "What four ?" asked the king. "A decrepit old man, a diseased man, a dead man and a monk - these four will make the prince retire from the world" replied the astrologers.

Suddhodana thought that he might lose his precious son and tried his level best to make him attached to earthly objects. He surrounded him with all kinds of luxury and indulgence, in order to retain his attachment for pleasures of the senses and prevent him front undertaking a vow of solitariness and poverty. He got him married and put him in a walled place with gardens, fountains, palaces, music, dances, etc. Countless charming young ladies attended on Siddhartha to make him cheerful and happy. In particular, the king wanted to keep away from Siddhartha the 'four signs' which would move him to enter into the ascetic life. "From this time on" said the king, "let no such persons be allowed to come near my son. It will never do for my son to become a Buddha. What I would wish to see is, my son exercising sovereign rule and authority over the four great continents and the two thousand attendant isles, and walking through the heavens surrounded by a retinue thirty-six leagues in circumference". And when he had so spoken, he placed guards for quarter of a league, in each of the four directions, in order that none of the four kinds of men might come within sight of his son.

Buddha's original name was Siddhartha. It meant one who had accomplished his aim. Gautama was Siddhartha's family name. Siddhartha was known all over the world as Buddha, the Enlightened. He was also known by the name of Sakhya Muni, which meant an ascetic of the Sakhya tribe.

Siddhartha spent his boyhood at Kapilavastu and its vicinity. He was married at the age of sixteen. His wife's name was Yasodhara. Siddhartha had a son named Rahula. At the age of twenty-nine, Siddhartha Gautama suddenly abandoned his home to devote himself entirely to spiritual pursuits and Yogic practices. A mere accident turned him to the path of renunciation. One day he managed, somehow or the other, to get out of the walled enclosure of the palace and roamed about in the town along with his servant Channa to see how the people were getting on. The sight of a decrepit old man, a sick man, a corpse and a monk finally induced Siddhartha to renounce the world. He felt that he also would become a prey to old age, disease and death. Also, he noticed the serenity and the dynamic personality of the monk. Let me go beyond the miseries of this Samsara (worldly life) by renouncing this world of miseries and sorrows. This mundane life, with all its luxuries and comforts, is absolutely worthless. I also am subject to decay and am not free from the effect of old age. Worldly happiness is transitory".

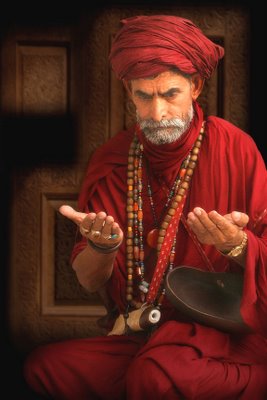

Gautama left for ever his home, wealth, dominion, power, father, wife and the only child. He shaved his head and put on yellow robes. He marched towards Rajgriha, the capital of the kingdom of Magadha. There were many caves in the neighbouring hills. Many hermits lived in those caves. Siddhartha took Alamo Kalamo, a hermit, as his first teacher. He was not satisfied with his instructions. He left him and sought the help of another recluse named Uddako Ramputto for spiritual instructions. At last he determined to undertake Yogic practices. He practiced severe Tapas (austerities) and Pranayama (practice of breath control) for six years. He determined to attain the supreme peace by practicing self-mortification. He abstained almost entirely from taking food. He did not find much progress by adopting this method. He was reduced to a skeleton. He became exceedingly weak.

At that moment, some dancing girls were passing that way singing joyfully as they played on their guitar. Buddha heard their song and found real help in it. The song the girls sang had no real deep meaning for them, but for Buddha it was a message full of profound spiritual significance. It was a spiritual pick-me-up to take him out of his despair and infuse power, strength and courage. The song was:

"Fair goes the dancing when the Sitar is tuned,

Tune us the Sitar neither low nor high,

And we will dance away the hearts of men.

The string overstretched breaks, the music dies,

The string overslack is dumb and the music dies,

Tune us the Sitar neither low nor high."

Buddha realized then that he should not go to extremes in torturing the body by starvation and that he should adopt the golden mean or the happy medium or the middle path by avoiding extremes. Then he began to eat food in moderation. He gave up the earlier extreme practices and took to the middle path.

Once Buddha was in a dejected mood as he did not succeed in his Yogic practices. He knew not where to go and what to do. A village girl noticed his sorrowful face. She approached him and said to him in a polite manner: "Revered sir, may I bring some food for you ? It seems you are very hungry". Gautama looked at her and said, "What is your name, my dear sister ?". The maiden answered, "Venerable sir, my name is Sujata". Gautama said, "Sujata, I am very hungry. Can you really appease my hunger ?"

The innocent Sujata did not understand Gautama. Gautama was spiritually hungry. He was thirsting to attain supreme peace and Self-realization. He wanted spiritual food. Sujata placed some food before Gautama and entreated him to take it. Gautama smiled and said, "Beloved Sujata, I am highly pleased with your kind and benevolent nature. Can this food appease my hunger ?". Sujata replied, "Yes sir, it will appease your hunger. Kindly take it now". Gautama began to eat the food underneath the shadow of a large tree, thenceforth to be called as the great 'Bo-tree' or the tree of wisdom. Gautama sat in a meditative mood underneath the tree from early morning to sunset, with a fiery determination and an iron resolve: "Let me die. Let my body perish. Let my flesh dry up. I will not get up from this seat till I get full illumination". He plunged himself into deep meditation. At night he entered into deep Samadhi (superconscious state) underneath that sacred Bo-tree (Pipal tree or ficus religiosa). He was tempted by Maya in a variety of ways, but he stood adamant. He did not yield to Maya's allurements and temptations. He came out victorious with full illumination. He attained Nirvana (liberation). His face shone with divine splendour and effulgence. He got up from his seat and danced in divine ecstasy for seven consecutive days and nights around the sacred Bo-tree. Then he came to the normal plane of consciousness. His heart was filled with profound mercy and compassion. He wanted to share what he had with humanity. He traveled all over India and preached his doctrine and gospel. He became a saviour, deliverer and redeemer.

Buddha gave out the experiences of his Samadhi: "I thus behold my mind released from the defilement of earthly existence, released from the defilement of sensual pleasures, released from the defilement of heresy, released from the defilement of ignorance."

In the emancipated state arose the knowledge: "I am emancipated, rebirth is extinct, the religious walk is accomplished, what had to be done is done, and there is no need for the present existence. I have overcome all foes; I am all-wise; I am free from stains in every way; I have left everything and have obtained emancipation by the destruction of desire. Myself having gained knowledge, whom should I call my Master ? I have no teacher; no one is equal to me. I am the holy one in this world; I am the highest teacher. I alone am the absolute omniscient one (Sambuddho). I have gained coolness by the extinction of all passion and have obtained Nirvana. To found the kingdom of law (Dharmo) I go to the city of Varnasi. I will beat the drum of immortality in the darkness of this world".

Lord Buddha then walked on to Varnasi. He entered the 'deer-park' one evening. He gave his discourse there and preached his doctrine. He preached to all without exception, men and women, the high and the low, the ignorant and the learned - all alike. All his first disciples were laymen and two of the very first were women. The first convert was a rich young man named Yasa. The next were Yasa's father, mother and wife. Those were his lay disciples.

Buddha argued and debated with his old disciples who had deserted him when he was in the Uruvila forest. He brought them round by his powerful arguments and persuasive powers. Kondanno, an aged hermit, was converted first. The others also soon accepted the doctrine of Lord Buddha. Buddha made sixty disciples and sent them in different directions to preach his doctrine.

Buddha told his disciples not to enquire into the origin of the world, into the existence and nature of God. He said to them that such investigations were practically useless and likely to distract their minds.

The number of Buddha's followers gradually increased. Nobles, Brahmins and many wealthy men became his disciples. Buddha paid no attention to caste. The poor and the outcastes were admitted to his order. Those who wanted to become full members of his order were obliged to become monks and to observe strict rules of conduct. Buddha had many lay disciples also. Those lay members had to provide for the wants of the monks.

In the forest of Uruvila, there were three brothers - all very famous monks and philosophers. They had many learned disciples. They were honoured by kings and potentates. Lord Buddha went to Uruvila and lived with those three monks. He converted those three reputed monks, which caused a great sensation all over the country.

Lord Buddha and his disciples walked on towards Rajgriha, the capital of Magadha. Bimbisara, the king, who was attended upon by 120,000 Brahmins and householders, welcomed Buddha and his followers with great devotion. He heard the sermon of Lord Buddha and at once became his disciple. 110,000 of the Brahmins and householders became full members of Lord Buddha's order and the remaining 10,000 became lay adherents. Buddha's followers were treated with contempt when they went to beg their daily food. Bimbisara made Buddha a present of Veluvanam - a bamboo-grove, one of the royal pleasure-gardens near his capital. Lord Buddha spent many rainy seasons there with his followers.

Every Buddhist monk takes a vow, when he puts on the yellow robe, to abstain from killing any living being. Therefore, a stay in one place during the rainy season becomes necessary. Even now, the Paramahamsa Sannyasins (the highest class of renunciates) of Sankara's order stay in one place for four months during the rainy season (Chaturmas). It is impossible to move about in the rainy season without killing countless small insects, which the combined influence of moisture and the hot sun at the season brings into existence.

Lord Buddha received from his father a message asking him to visit his native place, so that he might see him once more before he died. Buddha accepted his invitation gladly and started for Kapilavastu. He stayed in a forest outside the city. His father and relatives came to see him, but they were not pleased with their ascetic Gautama. They left the place after a short time. They did not make any arrangement for his and his followers' daily food. After all, they were worldly people. Buddha went to the city and begged his food from door to door. This news reached the ears of his father. He tried to stop Gautama from begging. Gautama said: "O king, I am a mendicant - I am a monk. It is my duty to get alms from door to door. This is the duty of the Order. Why do you stop this ? The food that is obtained from alms is very pure". His father did not pay any attention to the words of Gautama. He snatched the bowl from his hand and took him to his palace. All came to pay Buddha their respects, but his wife Yasodhara did not come. She said, "He himself will come to me, if I am of any value in his eyes". She was a very chaste lady endowed with Viveka (discrimination), Vairagya (dispassion) and other virtuous qualities. From the day she lost her husband she gave up all her luxuries. She took very simple food once daily and slept on a mat. She led a life of severe austerities. Gautama heard all this. He was very much moved. He went at once to see her. She prostrated at his feet. She caught hold of his feet and burst into tears. Buddha established an order of female ascetics. Yasodhara became the first of the Buddhistic nuns.

Yasodhara pointed out the passing Buddha to her son through a window and said, "O Rahula! That monk is your father. Go to him and ask for your birthright. Tell him boldly, 'I am your son. Give me my heritage'". Rahula at once went up to Buddha and said, "Dear father, give me my heritage". Buddha was taking his food then. He did not give any reply. The boy repeatedly asked for his heritage. Buddha went to the forest. The boy also silently followed him to the forest. Buddha said to one of his disciples, "I give this boy the precious spiritual wealth I acquired under the sacred Bo-tree. I make him the heir to that wealth". Rahula was initiated into the order of monks. When this news reached the ears of Buddha's father, he was very much grieved because after losing his son, he now lost his grandson also.

Buddha performed some miracles. A savage serpent of great magical power sent forth fire against Buddha. Buddha turned his own body into fire and sent forth flames against the serpent. Once a tree bent down one of its branches in order to help Buddha when he wanted to come up out of the water of a tank. One day five hundred pieces of firewood split by themselves at Buddha's command. Buddha created five hundred vessels with fire burning in them for the Jatilas to warm themselves on a winter night. When there was flood, he caused the water to recede and then he walked over the water.

Ananda, one of Buddha's cousins, was one of the principal early disciples of Buddha and was a most devoted friend and disciple of Buddha. He was devoted to Buddha with a special fervour in a simple childlike way and served him as his personal attendant till the end of his life. He was very popular. he was a very sweet man with pleasant ways. He had no intellectual attainments, but he was a man of great sincerity and loving nature. Devadatta, one of Ananda's brothers, was also in the Order. Devadatta became Buddha's greatest rival and tried hard to oust Buddha and occupy the place himself. A barber named Upali and a countryman called Anuruddha were admitted into the Order. Upali became a distinguished leader of his Order. Anuruddha became a Buddhistic philosopher of vast erudition.

Buddha went to Sravasti, the capital of the kingdom of Kosala. Here a wealthy merchant gave him for residence an extensive and beautiful forest. Buddha spent many rainy seasons there and delivered several grand discourses. Thus Lord Buddha preached his doctrine for over forty-five years traveling from place to place.

Buddha died of an illness brought on by some error in diet. He became ill through eating Sukara-maddavam, prepared for him by a lady adherent named Cundo. The commentator explains the word as meaning 'hog's flesh'. Subadhara Bhikshu thinks it means something which wild boars are fond of and says that it has something of the nature of a truffle. Dr. Hoey says that it is not boar's flesh but Sukarakanda or hog's root, a bulbous root found chiefly in the jungle and which Hindus eat with great joy. It is a Phalahar that is eaten on days of fasting.

Buddha said to Ananda, "Go Ananda, prepare for me, between twin Sal trees, a couch with the head northward. I am exhausted and would like to lie down". A wonderful scene followed. The twin Sal trees burst into full bloom although it was not the blossoming season. Those flowers fell on the body of Buddha out of reverence. Divine coral tree flowers and divine sandalwood powders fell from above on Buddha's body out of reverence.

Lord Buddha said, "Come now, dear monks. I bid you farewell. Compounds are subject to dissolution. Prosper ye through diligence and work out your salvation".

The spirit of Ahimsa (non-violence) was ever present with Gautama from his very childhood. One day, his cousin Devadatta shot a bird. The poor creature was hurt and fell to the ground. Gautama ran forward, picked it up and refused to hand it over to his cousin. The quarrel was taken up before the Rajaguru who, however, decided in favour of Gautama to the great humiliation of Devadatta.

In his wanderings, Gautama one day saw a herd of goats and sheep winding their way through a narrow valley. Now and then the herdsman cried and ran forward and backward to keep the members of the fold from going astray. Among the vast flock Gautama saw a little lamb, toiling behind, wounded in one part of the body and made lame by a blow of the herdsman. Gautama's heart was touched and he took it up in his arms and carried it saying, "It is better to relieve the suffering of an innocent being than to sit on the rocks of Olympus or in solitary caves and watch unconcerned the sorrows and sufferings of humanity". Then, turning to the herdsman he said, "Whither are you going, my friend, with this huge flock so great a hurry ?". "To the king's palace" said the herdsman, "We are sent to fetch goats and sheep for sacrifice which our master - the king - will start tonight in propitiation of the gods." Hearing this, Gautama followed the herdsman, carrying the lamb in his arms. When they entered the city, word was circulated that a holy hermit had brought the sacrifices ordered by the king. As Gautama passed through the streets, people came out to see the gracious and saintly figure of the youth clad in the yellow robes of a Sadhu (renunciate) and all were struck with wonder and awe at his noble mien and his sweet expression. The king was also informed of the coming of the holy man to the sacrifice. When the ceremonies commenced in the presence of the king, there was brought a goat ready to be killed and offered to the gods. There it stood with its legs tied up and the high priest ready with a big bloodthirsty knife in his hand to cut the dumb animal's throat. In that cruel and tragic moment, when the life of the poor creature hung by a thread, Gautama stepped forward and cried, "Stop the cruel deed, O king!". And as he said this, he leaned forward and unfastened the bonds of the victim. "Every creature" he said, "loves to live, even as every human being loves to preserve his or her life". The priest then threw the knife away like a repentant sinner and the king issued a royal decree throughout the land the next day, to the effect that no further sacrifice should be made in future and that all people should show mercy to birds and beasts alike.

Kisagotami, a young woman, was married to the only son of a rich man and they had a male child. The child died when he was two years old. Kisagotami had intense attachment for the child. She clasped the dead child to her bossom, refused to part with it, and went from house to house, to her friends and relatives, asking them to give some medicine to bring the child back to life. A Buddhist monk said to her: "O good girl! I have no medicine. But go to Lord Buddha. He can surely give you a very good medicine. He is an ocean of mercy and love. The child will come back to life. Be not troubled". She at once ran to Buddha and said, "O venerable sir! Can you give any medicine to this child ?". Buddha replied, "Yes. I will give you a very good medicine. Bring some mustard seed from some house where no child or husband or wife or father or mother or servant had died". She said, "Very good, sir, I shall bring it in a short time".

Carrying her dead child in her bossom, Kisagotami went to a house and asked for some mustard seed. The people of the house said, "O lady, here is mustard seed. Take it". Kisagotami asked, "In your house, has any son or husband or wife, father or mother or servant died ?". They replied, "O lady! You ask a very strange question. Many have died in our house". Kisagotami went to another house and asked the same. The owner of the house said, "I have lost my eldest son and my wife". She went to a third house. People of the house answered, "We have lost our parents". She went to another house. The lady of the house said, "I lost my husband last year". Ultimately Kisagotami was not able to find a single house where no one had died. Viveka and Vairagya dawned in her mind. She buried the dead body of her child. She began to reflect seriously on the problem of life and death in this world.

Kisagotami then went to Lord Buddha and prostrated at his lotus feet. Buddha said to her, "O good girl! Have you brought the mustard seed ?". Kisagotami answered, "I am not able to find a single house where no one has died". Then Buddha said, "All the objects of this world are perishable and impermanent. This world is full of miseries, troubles and tribulations. Man or woman is troubled by birth, death, disease, old age and pain. We should gain wisdom from experience. We should not expect for things that do not and will not happen. This expectation leads us to unnecessary misery and suffering. One should obtain Nirvana. Then only all sorrows will come to an end. One will attain immortality and eternal peace". Kisagotami then became a disciple of Buddha and entered the Order of Nuns.

Once Buddha went to the house of a rich Brahmin with bowl in hand. The Brahmin became very angry and said, "O Bhikshu, why do you lead an idle life of wandering and begging ? Is this not disgraceful ? You have a well-built body. You can work. I plough and sow. I work in the fields and I earn my bread at the sweat of my brow. I lead a laborious life. It would be better if you also plough and sow and then you will have plenty of food to eat". Buddha replied, "O Brahmin! I also plough and sow, and having ploughed and sown, I eat". The Brahmin said, "You say you are an agriculturist. I do not see any sign of it. Where are your plough, bullocks and seeds ?". Then Buddha replied, "O Brahmin! Just hear my words with attention. I sow the seed of faith. The good actions that I perform are the rain that waters the seeds. Viveka and Vairagya are parts of my plough. Righteousness is the handle. Meditation is the goad. Sama and Dama - tranquillity of the mind and restraint of the Indriyas (senses) - are the bullocks. Thus I plough the soil of the mind and remove the weeds of doubt, delusion, fear, birth and death. The harvest that comes in is the immortal fruit of Nirvana. All sorrows terminate by this sort of ploughing and harvesting". The rich arrogant Brahmin came to his senses. His eyes were opened. He prostrated at the feet of Buddha and became his lay adherent.

Lord Buddha preached: "We will have to find out the cause of sorrow and the way to escape from it. The desire for sensual enjoyment and clinging to earthly life is the cause of sorrow. If we can eradicate desire, all sorrows and pains will come to an end. We will enjoy Nirvana or eternal peace. Those who follow the Noble Eightfold Path strictly, viz., right opinion, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right employment, right exertion, right thought and right self-concentration will be free from sorrow. This indeed, O mendicants, is that middle course which the Tathagata has thoroughly comprehended, which produces insight, which produces knowledge, which leads to calmness or serenity, to supernatural knowledge, to perfect Buddhahood, to Nirvana.

"This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of suffering. Birth is painful, old age is painful, sickness is painful, association with unloved objects is painful, separation from loved objects is painful, the desire which one does not obtain, this is too painful - in short, the five elements of attachment to existence are painful. The five elements of attachment to earthly existence are form, sensation, perception, components and consciousness.

"This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the truth of the cause of suffering. It is that thirst which leads to renewed existence, connected with joy and passion, finding joy here and there, namely, thirst for sensual pleasure, and the instinctive thirst for existence. This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of cessation of suffering, which is the cessation and total absence of desire for that very thirst, its abandonment, surrender, release from it and non-attachment to it. This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of the course which leads to the cessation of suffering. This is verily the Noble Eightfold Path, viz., right opinion, etc."